![]()

![]()

Headingley Karate

|

|

|

Shu Points

by Zoltan Dienes & Mike Flanagan

Abstract

Pain ratings were obtained when a kyusho jutsu point - the target point - had been hit by itself, or when it was struck immediately after a set up point had been struck. In one condition, the set up and target points were "shu" points, which are points especially used by acupuncturists to manipulate qi according to the Five Elements. The two points were specially selected so that the qi imbalance caused by the set up strike should be aggravated by the target strike, according to the destructive cycle. In the other condition, the set up point and target point followed the destructive cycle, but they were not shu points. Sixteen subjects were tested in both conditions using a double blind procedure. We found that the set up did not increase the pain produced by the target strike, not even when shu points were used. In fact, the pain of the target strike was non-significantly lower after a set up strike had been given rather than no set up at all. The results do not support the commonly held idea that the destructive cycle predicts which points will be sensitized by other points in a martially useful way.

Introduction

Practitioners of Kyusho Jutsu will be very much aware that the effectiveness of attacking a given target point can be dramatically increased by first setting it up by an attack to an initial point or set of points. Why should some points set up other points? Many people have turned to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) to answer just this question. TCM is an ideal place to look for inspiration on relationships between kyusho jutsu points useful for martial purposes, because kyusho-jutsu points have substantial overlap with acupuncture points, and TCM contains the fruits of several thousand years of investigation into relationships between acupuncture points. By the same token, one cannot take for granted that a TCM-inspired theory of the use of points in martial arts automatically has the evidential support of thousands of years of history. TCM was field tested for improving people's health, not for martial arts, and every stage of extrapolation from health to martial arts needs to be rigorously tested. TCM - itself not a single monolithic body of knowledge - would allow a multitude of quite different extrapolations, no one of which is obviously correct. So it would seem a worthwhile endeavour to take concepts from TCM to inspire a theory of useful point combinations in martial arts; and then actually test the theory under controlled conditions.

The first stage, proposing a TCM inspired theory, has already been accomplished. Of course, there are many such theories that could be proposed, but there was one that achieved particular dominance in the kyusho community. To understand this theory, some basic concepts of traditional Chinese thinking need to be understood. According to traditional Chinese thought, there are five phases or elements in nature: fire, earth, metal, water, and wood. The elements are related by two cycles: The creative cycle and the control (or destructive) cycle. According to the creative cycle, fire creates or feeds earth (as fire makes ash), earth creates metal (metal is found deep in the earth), metal creates water (condensation), water creates wood (without watering, plants die), and wood creates fire. Conversely, according to the destructive cycle, fire burns metal, metal cuts wood, woods digs into earth, earth absorbs water, and water extinguishes fire. According to TCM, classical acupuncture points lie along 12 channels of qi flow, or meridians, and 10 of these meridians are associated with a particular element. Thus, most acupuncture points are associated with an element, by virtue of the meridian to which they belong.

The suggestion that gained prominence in the kyusho community was that point combinations that followed the destructive cycle would be particularly effective. For example, if one attacked a fire point (a point on a fire meridian), one should look for available metal points to attack next. Indeed, the effectiveness of particular combinations that followed the destructive cycle was easy to demonstrate. Nonetheless, there are many reasons why combinations would be effective. For example, the first strike may simply expose and make vulnerable the second target because of associated body movement: For example, hitting the brachioradialis muscle makes the head come forward and exposes the neck. Also, consider holding the wrist at H6 (fire) while striking LI10 (metal). Holding the wrist may make the strike more painful compared to just letting uke’s arm swing freely. But is that because fire burns metal or because the limb absorbs more force when held? In general, does activating one point actually make other points more sensitive in accordance with the destructive cycle when body movement and position (and expectations and beliefs) are controlled for?

In a first experiment (Dienes & Flanagan, 1999) we tested a group of people naive to TCM. We used a person (tori) to attack the points who had knowledge of kyusho jutsu but was completely ignorant about TCM. His ignorance of TCM meant that variations in the accuracy and pressure of the technique were not systematically related to the predictions of TCM (a very real hazard if anybody knowledgeable of TCM were to act as tori). On a given uke (experimental participant), tori pressed a ‘set up point’, released it, and immediately pressed a ‘target point’. The uke gave a pain rating to the target point on a standardized scale, where zero was no pain, and 10 was pain associated with a hard bang on the shin ("perhaps so painful that you had to sit down").

In the experiment, a sequence of a set up point followed by a target point could either follow the destructive cycle or the creative cycle. We chose one target point for each of the five elements; i.e. one metal one, one wood one, etc. Then for the set up points, we also choose one point for each of the elements. Tori was drilled on this small set of points until he could locate them quickly, accurately, and effectively.

During a karate session, individuals were taken aside individually and tested on a specific sequence. Twenty-eight people were tested on each element, both destructive and creative sequences. Over all five elements, the average pain rating given to the press on the target point was 6.0 for the destructive sequence. So subjects experienced a fair amount of pain; but is it any more than would be produced by any other sequence? In fact, the average pain rating for the creative sequences was 6.1. Statistical tests showed that there was no evidence that the small difference as did exist was due to anything other than the normal random variation in pain you might feel when the same technique is performed on you on two different occasions. Thus, this study provided no evidence that a particular sequence of the five elements is any more effective than any other sequence.

These results, however, do not rule out that following the destructive cycle may be useful under certain conditions, and knowledge of these conditions may be inspired by further concepts from Chinese medicine. Whereas in the kyusho world there is an implicit but prevalent belief that the destructive cycle can be followed by choosing any martially relevant point along a meridian, those acupuncturists who follow five element principles to manipulate the flow of qi, do so almost exclusively by the use of a particular set of points, the shu points on the lower halves of the arms and legs (e.g. Maciocia, 1989). This is not an absolute rule; some acupuncturists may use anywhere along the meridian, and shiatsu practitioners regularly use the whole meridian in using the five element cycles. Nonetheless, the shu points have the special function of influencing qi according to principles of the five elements, and so cross-point set up effects in kyusho jutsu according to the elemental cycles may be especially evident when these points are used, if such effects can be found at all. The aim of the current experiment was to test this idea.

To understand how the shu points work, we need to consider some more ideas from TCM. We will assume that a strike or press to a point on a meridian can tonify or sedate the qi of that meridian. Tonifying the qi means increasing the amount of qi; sedating the qi means decreasing the amount of qi. According to TCM, the optimal state of affairs is where there is a balance, neither too much nor too little qi in any meridian. Injury, harm or disease is associated with either too much or too little qi. Thus, through kyusho jutsu, our aim is to create either as great a deficiency or as great an excess as we can. Combinations that result in either of these states of affairs are optimal from a martial perspective.

There are special shu points for tonifying and sedating on each of 10 meridians. We will be using tonification and sedation points. We will also apply another principle mentioned by George Soulie de Morant (1994), namely “puncture with the needle tilted, with the point facing against the flow in order to disperse (this is opposing), the point going with the flow in order to tonify (this is favouring)” (p.103). Thus, we presume that stimulating in the direction of flow helps to tonify and against the flow helps to sedate, a principle used by some martial artists. Having so manipulated the qi of one element, the creative and destructive cycles determine how the qi of other elements will be affected. For example, if one element has been tonified, this will result in the next element in the creative cycle also being tonified, and the next element in the destructive cycle being sedated; conversely, if one element has been sedated, that will result in the next element in the creative cycle being sedated, and the next element in the destructive cycle being tonified. These principles will be used by us in the following way: A second attack that aggravates imbalances (too much or too little qi) caused by the first is a productive way of combining points.

As an aside, there is no reason why TCM should be applied in just this manner. We just do not know whether the principles developed in a healing setting can apply to the quite different martial arts setting. For example, tonification in the healing setting involves “careful pain-free needling with thin needles inserted in the direction of flow of the channel, gentle manipulation or none at all, and long retention of the needles (15-30 minutes). Quick insertion and slow withdrawal of the needles is also tonifying” (Stux and Pomeranz, 1998, p. 205). Nothing like the martial application 'thump in the direction of flow to tonify'. That ‘s not to say the principles do not apply as stated above; just that it is FAR from obvious they apply so directly. Careful testing of each and every principle is needed. We will be testing one possible use of TCM principles, a use which is consistent, if not identical in principle, with the use we have seen some martial artists actually make of TCM to kyusho jutsu.

In the experiment, as people practiced their basic punch, kick etc, tori (i.e. the person who administered the experimental procedure) walked round testing each person in turn. Unlike in the previous experiment where points were pressed, in this experiment points were hit, based on a view some kyusho practitioners have that hitting points is more likely to activate them than pressing them. For a given sequence, uke could be hit either without a set up point, just the target point is hit; or he could be hit with first a set up point and then a target point. Will the target point be more painful when it was been set up by another point rather than when the target is just hit alone? Will shu points be better set up points than the sort of points we used in our first experiment ("vanilla" points)?

Method

Participants

The participants (ukes) were 16 students attending a karate class at the University of Sussex Shotokan Karate Club.Design Two types of point sequences were used: sequences containing shu points; and sequences containing "vanilla" points, i.e. points which did not fall into a formal TCM category (e.g. shu, xi, mu, connecting, etc). We had one shu target and one shu set up point; and one vanilla target with one vanilla set up, described below. Each uke was tested on both shu and vanilla sequences, but with at least a 20 minute break between each sequence. In the first block of testing, an uke was tested on a target alone and also, with at least a 20 minute gap in between, with the target preceded by the set up but this time on the other side of the body. Here some ‘counterbalancing’ variables came in, the conditions of which each uke was randomly assigned. The first counterbalancing variable was shu order (half the ukes were tested with the shu sequence in the first block, half with the shu sequence in the second block). For the first and second blocks separately the following was counterbalanced: target alone order (was the target alone struck first; or was the set up-target sequence struck first); left/right (half the ukes were first tested on the right side and then the left side; the other half of the ukes were tested first left and then right) - we did not strike exactly the same point again in the experiment in case there was residual local sensitivity, bruising, etc from the first strike. In addition, between the blocks, we counterbalanced the pairing of target alone order in the first block with the target alone order in the second block. There were thus four counterbalancing variables, making 8 cells in the design. There were two ukes in each cell. The pairing of left/right first in the first block with left/right first in the second block was free to vary randomly. The 16 precise orders of blows for each uke were drawn up in advance of testing and ordered randomly according to a random number generator. Ukes were then tested in that pre-determined random order.

Before the experiment was run, tori practiced the points on different ukes for several sessions, so that he could hit the exact points accurately and in a standard way. Tori and all ukes did not know how to classify points according to their associated elements and did not know the point of the experiment; i.e. the experiment was run "double blind".

Points Used

| set up | target | |

| 'Vanilla' | H2 (fire) | Lu4 (metal) | 'Shu' | TW3 (fire) | Lu5 (metal) |

As can be seen, in both sequences the destructive cycle was followed ("fire burns metal"). Consider now the shu sequence. TW3 is the tonification point for the TW (triple warmer) meridian. Thus, striking TW3 would lead to an increase in fire qi. By the destructive cycle, metal qi is sedated. Lu5 is the sedation point for the Lu (Lung) meridian. Thus, striking Lu5 should aggravate the existing deficiency in Lu (metal) qi, making this strike particularly effective. Note that the set up point was struck in the direction of qi flow, and the target point was struck against the flow. All these points are points that are used by martial artists.

Instructions to participants During this session, Jez will approach you a couple of times. We are testing some theories about how different pressure points elicit pain. If you don't want to participate that is fine, just say so when he approaches you. If you have any medical conditions you should not participate. He will simply strike either just one pressure point on you or two in succession. You may not feel anything, or you may feel some more or less moderate pain. You will be asked to give a pain rating to each strike. If you feel no pain, then give '0' for your pain rating. Now I want you to imagine some time you banged your shin or ankle, or stubbed a toe. Imagine a time when it was really very painful, so painful you wanted to sit down. If you can't remember a specific episode, that's fine, just imagine what it would be like. That amount of pain we call '10'. I will give you 10 seconds now to choose and clearly fix in your mind how much pain a '10' feels like .... that's good. If when you are struck you feel that amount of pain, then say '10'. If half that amount of pain then say '5'; if twice that amount say '20', and so on.

Results

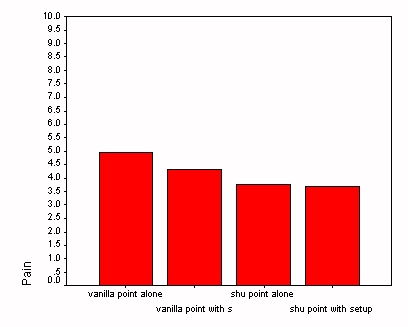

Figure 1 shows the mean pain ratings for the ukes for the target vanilla point alone and preceded by set up; and for the target shu point alone and preceded by set up. It can be seen that the target point is no more painful after a set up than after no set up.

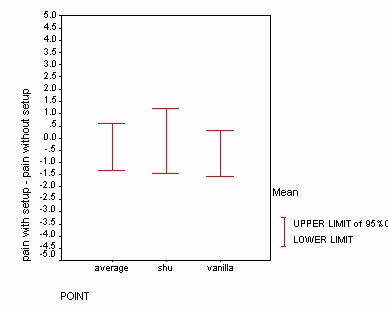

How sensitive was the experiment to pick up on any real differences that may have existed? Figure 2 shows the sensitivity of the experiment. The graph shows the difference in pain with set up and pain without set up. If a set up causes more pain in the target point than the target point attacked alone, this difference would be positive. The difference for our sample means happens to be negative, but that sample difference is consistent with a range of population differences (a sample in general does not exactly reproduce the means of the population). The graph shows the range of population differences our sample difference is consistent with (to be precise: the set of all population differences the sample is non-significantly different from with a one-sample t-test at the 5% level; i.e. the range shown is the 95% confidence interval). For example, if we take the data averaged over shu and vanilla points, the REAL population difference could be -1.3 (set up makes the target point less sensitive to pain by 1.3 pain points) or as high as 0.6 (set up increases the pain sensitivity by 0.6 pain units). This range includes zero, so we have no evidence that the set up made any change to the pain sensitivity of the target. Further, if it did make a difference, we can be 95% sure, roughly speaking, that it did not make the target point more sensitive than about 0.6 pain points. This is not very much. In other words, we can say the experiment ruled out set up effects with a high degree of sensitivity.

Although obvious from Figure 2, we also formally tested whether the shu set up effect was any different from the vanilla set up effect; it was not, t(15) = 0.89, p = 0.39.

Discussion

The aim of this experiment was to determine if a target point could have increased pain sensitivity when a set up point was struck first as compared to when the target point was struck alone. In particular, we chose points to follow the destructive sequence, a sequence often quoted in the kyusho community as making effective martial combinations. In a previous experiment (Dienes & Flanagan, 1999) we found that following the destructive sequence was no more effective than following the creative sequence for points belonging to no formal TCM category ("vanilla" points). It may be that this previous experiment did not obtain significant results because special points have to be used; the five element cycles may not usefully apply to any old vanilla point. Thus, in this experiment we contrasted vanilla points with shu points, points that are specially used in conjunction with the five element cycles in TCM healing practice. Further, in this experiment we compared set up with no set up, unlike in the previous experiment where there was always a set up. If shu points are particularly useful for manipulating qi according to the elemental cycles, one might expect a set up effect for the shu points which is larger than the set up effect for the vanilla points.

In fact, to our surprise, we found no set up effects at all, to a high degree of sensitivity. This is prima facie strong evidence against the common view that the destructive cycle provides a useful model for predicting cross point sensitization.

A critic of our study might argue that the qi had been disrupted in a nasty way by our point combination, it just did not express itself as pain sensitivity. In fact, to address this type of concern, we did try to measure heart rate changes in the experiment, using a Polar Heart Rate Monitor (which is portable and as accurate as an electrocardiogram). Sustained pain is known to produce sustained changes in heart rate (e.g. Gray, Watt, & Blass, 2000). Based on a few pilot subjects, however, we found that a one-off hit or two quick hits did not produce reliable changes in heart rate. In seems that the subjects own reported subjective pain experience was a more sensitive measure of the effect of the hit than heart rate. While we agree that other measures of qi disruption would be useful, we see no principled reason why pain should not be used as a measure. While some points produce reflex effects that occur quite independently of pain (e.g. attacks to the golgi apparatus of various muscles; Miller, 2000), we used points that gave a good pain reaction. If one wanted to argue that the pain had no relation to qi disruption, that would curtail the application of TCM ideas to a limited set of points or reactions to points. In fact, in a health setting, TCM is frequently applied to a problem showing itself through pain, and the application of TCM leads to the reduction of pain. Presumably, there is no reason why in a martial setting, if TCM applies at all, it can be applied to the task of increasing pain.

If the five element cycles do not provide a useful model for predicting cross point sensitization, other ideas from TCM may prove useful. For example, does striking along the same meridian sensitize points along that meridian? Does hitting one point sensitize the same contralateral point (there was some evidence for this in Dienes & Flanagan, 1999)? Similarly, concepts from modern western medicine may be useful. Does striking a trigger point sensitize points along its referral pathway (Baldry, 1998)? Future research will need to address these questions.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Rick Clark, Brian McCarthy, and Steven Webster for valuable discussion.

References

- Baldry, P. E. (1998). Acupuncture, trigger points and musculoskeletal pain :a scientific approach to acupuncture for use by doctors and physiotherapists in the diagnosis and management of myofascial trigger point pain, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- Dienes, Z., & Flanagan, M. (1999). Five element sequences. In the articles section of this website.

- Gray, L., Watt, L., & Blass, E. M. (2000). Skin-to-skin contact is analgesic in healthy newborns. Pediatrics, 105 (1).

- Maciocia, G. (1989). The foundations of Chinese medicine: a comprehensive text for acupuncturists and herbalists. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- Miller, B. (2000). Reflex pressure points: The hidden secret. MN: CME Publications.

- Soulie de Morant, G. (1994). Chinese acupuncture. Translation of L'acuponcture chinoise. Brookline: Paradigm,1994

- Stux, G., & Pomeranz, B. (1997). Basics of acupuncture. 4th rev. ed Berlin:Springer.